In my last post on the topic, we explored how ambition is one of the most pervasive, yet polarizing and misunderstood concepts in Western culture. The few historians and researchers who study the concept echo this idea. One such exponent is William Casey King, currently the Director of Capstone Programs at Yale's Jackson Institute for Global Affairs. In Ambition, a History: From Vice to Virtue, King discusses ambition's history and the mercurial, ever-evolving attitudes surrounding it. This article supplements King's fascinating history with independent research and analysis.

Ambition was not passed down through the centuries undisturbed like a precious treasure. Something approximating ambition appears in antiquity, a blurry but provocative concept. Seismic political and religious shifts cast it into a dark age where it was suppressed, oversimplified, and demonized. But ambition slowly rose from its underworld as it was dissected and discussed by great thinkers and statesmen, regaining its nuance and potentiality. Then, with the discovery of the New World, it entered a new stage of life. Ambition became a vivid and substantial concept, albeit one with complex, diametrical connotations.

Here we’ll explore ambition’s journey through the ages, the origins of its puzzling duplexity, and the important implications for us today.

Note: This post will get cut off in most email clients, so click here to read it in your browser

Ambition in Antiquity

From fictional characters like Gilgamesh and Achilles to the real-life sagas of Alexander and Caesar, ancient narratives are rife with tales of ambition. The world has long been fascinated by glory-hungry heroes who launch themselves into epic adventures, tests of will, and tragic struggles. From afar, we admire their superhuman resolve and tenacity while studying their hamartia. In such stories, every rise gives way to an equal and inevitable fall, leaving us with dramatic ambivalence toward the protagonists' plot-driving ambition.

We explored how the archaic Myth of Icarus encapsulates our thorny relationship with ambition: The master craftsman Daedalus and his son Icarus, imprisoned by a tyrannical king, plot their escape. Daedalus fashions two pairs of wings, using beeswax to bind feathers to a leather frame. Before their escape, he cautions Icarus not to fly too close to the sun, warning that the heat will melt the wax. Sure enough, Icarus, intoxicated by the thrill of flight, disregards his fathers warnings and soars high into the heavens. His wings melt and he plummets into the sea and drowns, becoming an enduring warning against hubris and untempered ambition.

However, in this parable there is a conveniently neglected counter-warning: Icarus was also advised against flying too low, for fear that the ocean mist would clog his wings and drag him into the water.

The ancient Greeks recorded Myth of Icarus over two thousand years ago, yet we still live with the same muddy, contradictory attitudes toward ambition. In the subsequent centuries, attitudes have transformed, blurred, lost and regained their nuance, and grown in complexity, all without ever losing their import.

King observes that the ancient Greeks had no exact equivalent of the word ambition. Their closest approximations were philotimia (“the love of honor”), eritheia (“rivalry” or “strife”), and philodoxia (“love of acclaim”). Hellenistic philosophers were divided in their views on "passions" like ambition. The Peripatetic school saw them as winds that moved human beings from inertia into action. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle stressed the "reciprocity of virtues," the need to cultivate and balance an array of virtues, for example, developing magnanimity to counterbalance philotimia. The Stoics, however, perceived the passions as violent, destructive currents within the human spirit.

In ancient Rome, the Latin ambitio was used to describe political candidates who traveled around canvassing votes. Modern Latin dictionaries variously associate ambitio with “a going about - especially of candidates for office;” “the soliciting of votes;” or a striving for honors, favor, adulation, and popularity. However, in ancient Roman law, charging a public figure with ambitus meant accusing them of political corruption.

Rome, of course, is one of the ancient civilizations most closely associated with ambition. The glory-obsessed Romans celebrated something akin to modern ambition, and actively cultivated it. For example, in the atrium of their homes, many noble Roman families displayed imagines, or lifelike funeral masks depicting their ancestors. These imagines maiorum ("images of the great ones") detailed the honors and accomplishments of a family's lineage with the intention, in part, of stoking descendants’ ambition. Importantly, the honorable ambition they fostered had a collectivist hue - anything done for the “Glory of Rome” - which no doubt helps explain Rome’s preoccupation with politics, commerce, expansion, and conquest.

However, the Romans were wary of ambition’s duality. Cicero described ambition as a “malady,” albeit one that draws “the greatest souls” and “most brilliant geniuses.” Similarly, Quintilian wrote “Though ambition may be a fault in itself, it is often the mother of virtues.” Seneca’s Stoic view was even more dogmatic, conjoining ambition with avarice, and dismissing them as outright “ills of the human soul.”

One could make the case that ambition not only fueled Rome’s ascension to greatness, but also engendered its demise. In the fourth century, as political instability and corruption induced classical Rome’s protracted deterioration, Saint Ambrose described ambition as a pestis occulta (“hidden plague”). Thus a shift began toward a more rigid version of ambition — one not only devoid of nuance, but also turned against the populace.

Ambition as Sin

A more recognizable conception of ambition appears as antiquity gives way to Christendom, and the Roman vice blurs into Christian sin.

The Geneva Bible, England's primary Bible through the 16th century, contained abundant marginal notes intended to help the average devotee interpret the text. In these annotations, ambition is condemned from the start, blamed for precipitating original sin itself: In the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve violated God's most important decree when they ate from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. The Geneva interpretation explained that Adam ate the fruit “Not so much to please his wife, as moued [sic] by ambition at her persuasion.” God reproaches their corruption and banishes them from paradise. Throughout the marginal notes that follow, ambition finds itself tethered to hostile terms like “malice,” “wicked desires,” “rage,” and “crueltie.” For the avoidance of doubt, one note declares explicitly, “God detesteth ambition.” To address supposedly sinful ambitious impulses, the annotators suggest not tempering it with virtues like humility or charity, but resignedly embracing “mediocritie."

Through the sixteenth century, this rhetoric was rampant in Western culture. Homilies, stories, poetry, and ballads propagated an ideology that human beings were bound to their station, whether they were a monarch by God-given right or a lowly serf like their forbearers. A restless desire to divert from the status quo, to rise above the “estate” which “God hath geven or appoynted,” was akin to rebellion, not unlike Adam and Eve’s original rebellion against God. It was an era that epitomized our modern conception of the “fixed mindset,” and ambition was implicitly and explicitly condemned. Not even Machiavelli, of all people, would try to save it — writing around the same time, he also vilified ambizione, coupling it with unsavory qualities like violence, corruption, and envy.

In the medieval world, the ruling class maintained power, in part, through hegemony and coercion. They subverted any sense of ambition among the lower classes and created conditions that made upward mobility unfathomable. Given the interlinkage of church and state, moral and religious misconduct was considered criminal activity, and brutal punishments and penalties were imposed to reinforce the community's behavioral expectations. Economic conditions were dreadful for society’s lower strata, and made worse by ever-increasing taxation to support domestic and foreign wars. When the climate became truly intolerable and peasant uprisings ensued, they were suppressed with the utmost violence. Pitifully, such revolts were not driven by the desire for ascension or dominion, but often for gentler treatment and, as if foreshadowing revolutions to come, a more reasonable approach to taxation.

Was hegemony an illustration of wicked ambition among the ruling class? Not quite. As I explained in our introduction to the topic, there is an important distinction between ambition and the desire to obtain and preserve power. The dogged maintenance of the status quo was a tyrannical expression of power, the desire of the ruling class to maintain their hierarchical standing through propaganda and pressure rather than prestige and competence. To maintain their dominion, they suppressed ambition among the lower classes, sacrificing any invention and ingenuity that might have accompanied it.

Ambition’s Renaissance

The hegemonic “Ambition as sin” ideology persisted through the seventeenth century. It helped sustain a vast socio-economic class disparity and rigid status hierarchy built not on merit, but hereditary entitlements. Like “communist” in the Cold War era, in early modern England “ambitious” was a damning buzzword.

At this stage in history, ambition is examined in drama. Picking up where the classical Greek tragedians left off, Elizabethan and Jacobean theater often featured ambitious anti-heroes subverting the natural order, rising above the prescribed limits of their birth, and inevitably leaving a trail of chaos in their wake. With their enemies waiting in the wings, the hero's virtues inevitably melt away, leaving only a raw, cankerous underbelly of passions, vices, and overplayed strengths. Fate tugs them back to earth like a cosmic bungee cord, and order - or some version of it - is once again restored. For example:

Macbeth succumbs to the siren call of ambition and becomes its slave. He loses his humanity, and then his head.

On the Ides of March, the illustrious Julius Caesar is betrayed and stabbed to death by his envious and morally dissonant companions.

After a Machiavellian rise to power, the initially amusing King Richard III suffers a short, paranoid, chaotic reign before dying on the battlefield.

Shakespearean scholar Robert Watson explains that in these tragedies, ambition is a “Sisyphean task… a perpetual quest for elevation that is baffled by some moral equivalent of the law of gravity.”

However, English historian Lawrence Stone labels this same period as England’s “century of mobility.” This raises the question: did these tragedies truly characterize ambition as an irredeemable sin, or as a potentially virtuous vice that demanded restraint? On the surface, dramatist like Shakespeare portrayed ambition as the bringer of corruption, tumult, and tragedy. However, a more nuanced interpretation suggests that they warned against unbridled ambition, coupled with perverse ethics and motives, and drew a Macbeth-shaped line in the sand with the notice: DO NOT CROSS — STEEP DROP AHEAD.

Either way, we can envision an uneasy audience brooding after the show, ruminating on the story’s moral lessons yet keenly aware of that latent fire in their own belly. We can imagine their guilt, their fear of providential punishment, their frustration at the futility of repressing that all-too-human drive of ambition. But perhaps, like their ancient, fire-harnessing progenitors, they imagined a way to corral and channel the flame of ambition. But how?

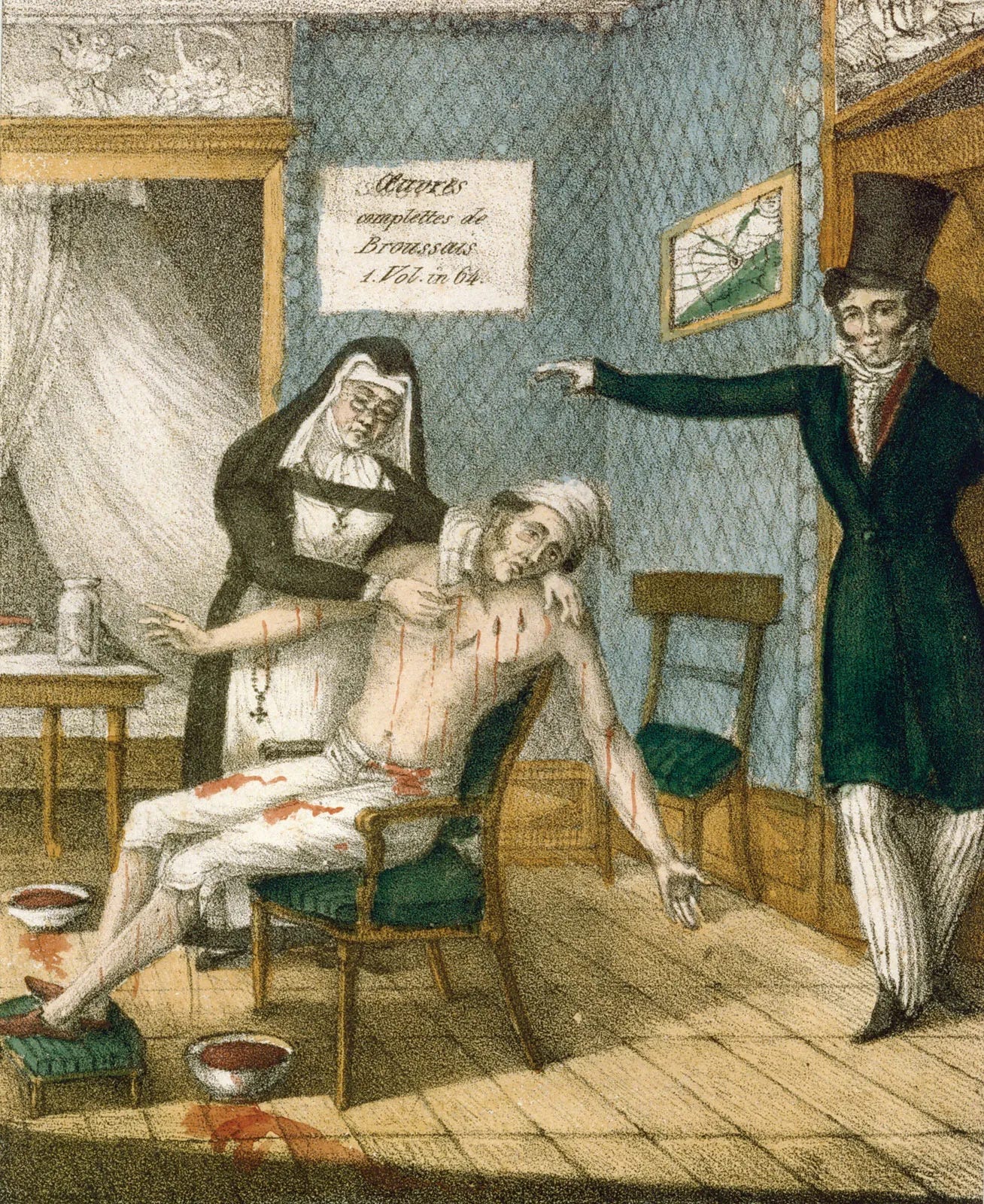

Ambition as Illness

For much of human history, illness was viewed as the embodiment of sin. Disease was often interpreted as divine retribution for immorality and the corruption of one’s soul.

Beliefs about the divine origins of pestilence stretch back at least 4,000 years to the Ancient Egyptians, who wrote that gods, demons, and spirits caused illness, and often prescribed prayer as a remedy. Ancient medical writing also suggested that illness - whether physical, spiritual, or moral - could be treated by bringing the body into balance, or what the ancient Greeks called eucrasia. Humoral theory posited that human beings consisted of four humors, bodily fluids which must be kept in equilibrium. Significantly, this is paralleled in Traditional Chinese Medicine, with Yin and Yang, its famous doctrine of balance, and a focus on the Five Elements within the body. Even in the present day, all manner of supplements, drugs, health regimens, and other remedies are successfully marketed under the pretense of “restoring balance.”

According to humoral theory, the slight dominance of one humor shaped an individual’s temperament, while a significant imbalance caused disease. To promote balance and restore wellness, physicians employed four strategies:

Clearing “stoppages” and allowing humors to properly “vent,” which was thought to prevent putrefaction.

Draining excess humors through infamous methods like purging, bleeding, or leeching.

Neutralizing imbalances by introducing a positive element, like healthful remedies, herbs, medicines, and prayer.

Employing the principle of countervailing, where disease was neutralized with equally powerful toxins or “passions." This often literally meant poison was used to counteract poison — perhaps a primitive ancestor to the practice of immunization.

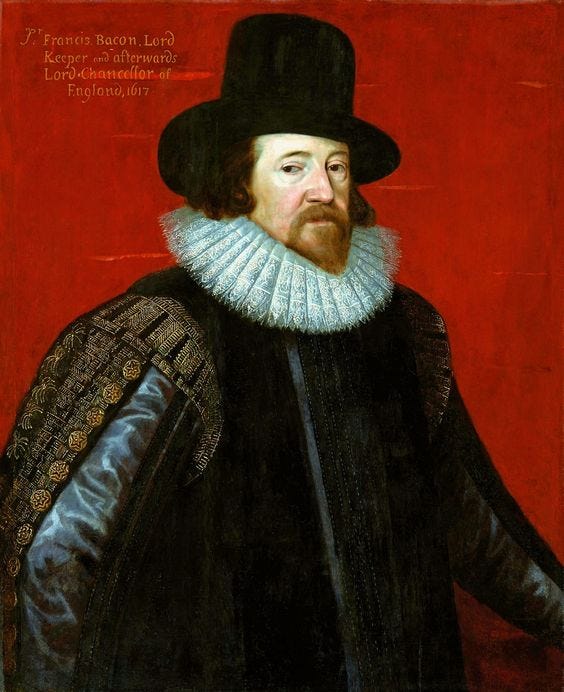

Francis Bacon, the English philosopher and statesman who profoundly influenced America’s Founding Fathers (a connection we will revisit shortly), applied these principles not only to medicine but also to the human psyche. Writing amidst the ravages of the bubonic plague, he proposed various humoral remedies for the Black Death, including carrying “little bladders of quicksilver, or tablets of arsenic, as preservatives against the plague,” on the theory that “being poisons themselves, they draw the venom to them from the spirits.” This exemplifies the principle of countervailing—using one toxin to neutralize another.

Bacon extended the humoral framework beyond physical disease, applying it to human vices and passions, particularly ambition. He explained that ambition, if allowed to circulate freely, “maketh men active, earnest, full of alacrity, and stirring.” However, if it is stifled - if the humor could not properly “vent” - Bacon posited that ambition becomes “malign and venomous,” causing people to “look upon men and matters with an evil eye” and be “best pleased, when things go backward.” However, “if they find the way open for their rising, and still get forward, they are rather busy than dangerous.” The argument aligns with the belief that a humoral blockage could cause distemper, and suggests the strategy of “venting” as a remedy.

Bacon also recognized that unchecked ambition could be dangerous, and his proposed solution reflects the humoral strategy of countervailing. He advised statesmen to balance the ambitions of one man against the other, explaining that “the best remedy against ambitious great-ones” is to “balance them by others, as proud as they.” Just as a physician might combat poison with poison, a statesman could neutralize a potential usurper by pitting him against an equally ambitious rival.

Despite his warnings about the perils of ambition, Bacon also acknowledged its potential virtues. In Novum Organum, Bacon explicitly discussed the existence of a “noble ambition,” which he described as any “endeavour to establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe.” This perspective suggested that ambition, like the humors, was not inherently good or bad — its effects depend on how it is managed.

Francis Bacon was not the only intellectual who merged physical and spiritual ailments and their treatment. In that era, remedies for both were discussed side-by-side in medical works without any suggestion of incongruity. In a seventeenth century medical text by clergyman Thomas Adams, the author compared ambition to the excess of choler and “immoderate thirst,” both of which benefitted from similar corrective measures. “To cure the immoderate Thirst of Ambition,” he advised, “let him take from God this prescript: He that exalteth himselfe, shall be brought low: but he that humbleth himselfe, shall be exalted… the first step to heaven’s court is humilitie.”

This illustrates a major shift in the conception of ambition — rather than a sin and rebellion against God, ambition is framed as a condition to be moderated and, in some cases, even harnessed for the greater good. Interestingly, and in contrast to the annotators of the Geneva Bible, Adams suggested that humility, rather than embracing mediocrity, was the right prescription to countervail ambition. Thus ambition regained some of its ancient nuance, and the previously black-and-white concept once again showed shades of gray.

Rebranding Ambition

Let’s rewind back to our imaginary Shakespearean audience. Recall them leaving the theater after a showing of Macbeth or Julius Caesar, reflecting on the overt moral of the story: ambition leads to destruction. But their unease is palpable. Domestically, economic mobility - once unthinkable - is becoming a tantalizing possibility. The rigid social order shows its first signs of fraying. Somewhere inside them, the long-stifled wick of ambition begins to smolder.

But an even more electrifying prospect looms beyond the horizon: the New World. A vast, uncharted continent, overflowing with natural resources, fertile land, unbounded opportunity, and the possibility of new beginnings. For the first time, the prospect of wealth and status, once confined to the nobility, is within the grasp of an enterprising commoner. It’s enough to set even the most temperate, God-fearing man's ambition ablaze.

To exacerbate the cognitive dissonance, around this time national governments - once the enforcers of ambition’s moral condemnation - did a complete one-eighty. They began to actively encourage and exploit ambition, using it as a tool to facilitate colonization. The Americas were portrayed as a land of limitless opportunity, where even a commoner could claim fortune, power, and prestige. Stories spread of vast, unclaimed tracts of land, fertile soil with flourishing crops, and rivers teeming with gold. Monarchs dangled noble titles as bait, enticing enterprising men to set sail. England, for example, created the title Knight Baronet of Nova Scotia to lure settlers, while multiple polities sold aristocratic titles to bolster their treasuries and fund expansion.

What was once condemned as an unspeakable vice became an instrument of empire. Columbus and his sponsors sought wealth and renown. The Jamestown colony was established by London's Virginia Company not as a religious refuge, but to turn a profit for investors. The conquistadors’ insatiable expansionist drive enriched Spain beyond imagination. France established trading posts throughout present-day Canada to export furs to Europe. The Netherlands, a small country but a naval powerhouse, established the Dutch East India Company which became, according to many accounts, the largest company in recorded history. All along the way, missions were established throughout the New World to convert Native Americans to Christianity. Once an unspeakable sin, the common man's ambition became a vehicle for winning territory, saving pagan souls, and accumulating resources in service of the state.

Following a trajectory openly endorsed by monarchs, ambitious individuals could suddenly buy or colonize their way into the aristocracy, making upward mobility more accessible and accepted than ever. While the quality was not explicitly recognized or recommended, it was rewarded and exploited nonetheless. The once-maligned trait became a servant of God, gold, and glory.

It was an unprecedented change with deep repercussions for the all involved. Once ambition was unleashed, like the opening of Pandora's box, it could not be undone. It had transformed from vice to sin, from sin to sickness, from sickness to autocratic asset, and it would soon transform again into something new and far more disruptive — reshaping societies, challenging hierarchies, and setting the stage for revolutions yet to come.

Ambition and the Birth of a Nation

The American Revolution was, as King describes, one of history’s “most audaciously ambitious acts.” By then ambition's once-toxic reputation had softened. Once scorned as a rebellion against the divine order, ambition became an ambivalent concept. Thus, an act of rebellion against the throne - an institution ordained by God - could be viewed with ambivalence rather than complete disdain, and framed in terms of principle rather than treachery. The changing zeitgeist made the pursuit of independence more palatable.

But ambition had not entirely shed its negative connotations. Of this, the Founding Fathers were well aware, and made every effort to frame the Revolution not as a reach for power and dominion, but as a virtuous imperative, a last resort, an inescapable battle of good versus evil. John Hancock made the case that "Resistance to tyranny becomes the Christian and social duty of each individual." In Practical Agitation, John Jay Chapman wrote that drastic action "is sometimes needed, and wisdom then approves it after the event. People who love soft methods and hate iniquity forget this,—that reform consists in taking a bone from a dog."

According to the Founders, real freedom could not be won without a fight. America was the virtuous underdog, long harassed and provoked, now finally striking back against an overreaching bully.

The Founders painted themselves not as scheming rebels but as humble citizen-servants caught in the midst of a noble struggle, duty-bound to act. George Washington was no ambitious general, he was a modern-day Cincinnatus. Benjamin Franklin was not a power-hungry politician, he was a rustic "natural man." Jefferson's ideal government was not an all-powerful empire, but a small, hands-off republic that was "rigorously frugal and simple."

But inevitably, playing down ambition’s role in the Revolution was a Sisyphean task. Thus America's forefathers began a wholesale rebranding campaign for ambition, promoting a more altruistic version of the trait - not unlike Francis Bacon's "noble ambition" - while doubling down on the argument that England had forced their hand. Thomas Paine's Common Sense contended that America did not start the war, "the first musket that was fired against her." He insisted that the War of Independence was not "drawn by caprice, nor extended by ambition; but produced by a chain of events, of which the colonies were not the authors." He characterized monarchy as a false, tyrannical system of government, and accused the church that supported it of corruption, castigating ambition's two biggest detractors in one fell swoop.

Writing in 1777, John Adams went further still, saying:

"Ambition in a Republic, is a great Virtue, for it is nothing more than a Desire, to Serve the Public, to promote the Happiness of the People, to increase the Wealth, the Grandeur, and Prosperity of the Community. This, Ambition is but another Name for public Virtue, and public Spirit."

Addressing the Pennsylvania Legislature, George Washington echoed the sentiment, arguing that ambition should not be about personal gain but a duty to something greater:

"It should be the highest ambition of every American to extend his views beyond himself, and to bear in mind that his conduct will not only affect himself, his country, and his immediate posterity; but that its influence may be co-extensive with the world, and stamp political happiness or misery on ages yet unborn."

Together they insisted that freedom, not hereditary succession, was a God-given right. Tyranny, not ambition, was the real sin. The United States of America became proof positive of ambition's immense generative potential. It was not a sin, a sickness, or a destructive force, but a catalyst for freedom.

Muddy, Modern Ambition

While the Founding Fathers publicly endorsed a noble, benevolent ambition, they remained privately conflicted about its true nature. Writing confidentially to Samuel Adams in the midst of the war, John Adams proposed, “The two Passions of Ambition and Avarice, which have been the Bane of Society and the Curse of human Kind, in all ages and Countries, are not without their Influence upon our Affairs here.” His rhetoric mimics Seneca's almost exactly — unsurprising, given the deep classical influences on America's founders. Alexander Hamilton struck a similar note in a letter to James Bayard, warning that, “Great ambition, unchecked by principle, or the love of Glory, is an unruly Tyrant... Ambition without principle never was long under the guidance of good sense.” Even George Washington, in a discarded draft of his inaugural address, warned that the young republic could be toppled by the combination of boundless ambition and corrupted morals. He argued that future Americans should be guided "by principles of true magnanimity" while guarding against the false ambitions of past empires, which sought to elevate themselves "at the expence of the freedom & happiness of the rest of mankind."

Outwardly, the Founders championed ambition as an essential force in building the nation. Privately, they feared its excesses and stressed the necessity of tempering it with virtue and principle. They also created structures to keep ambition in check, mirroring the old strategy of countervailing humors. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” James Madison famously wrote in The Federalist Papers, advocating for a system of checks and balances that would prevent any one individual’s ambition from overrunning the fledgling Republic.

Ultimately, the Founding Fathers crystallized their views on ambition and the appropriate aims of American citizens in the Declaration of Independence. In recognizing the unalienable rights of Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness, the Founders acknowledged the historical tendency of governments to violate these rights rather than safeguard them, and set an expectation for every citizen: to pursue their own fulfillment, so long as their ambition did not infringe upon the freedoms of others. Implicit in this famous statement is the recognition that ambition was a natural and powerful driver of human behavior and must be channeled, intentionally, in the most positive conceivable direction. To America's forebears, ambition was simultaneously a virtue and a vice, a core component of the national character but a potentially corruptive force, a powerful driver that required unyielding checks and balances on both the individual and institutional levels.

However, the Founders’ vision was not free of contradiction. As they publicly denounced British tyranny and the colonies’ lack of representation, many were slave owners and husbands to women with no political voice. The so-called universal right to pursue happiness was, in practice, reserved for a select few. Centuries would pass before the descendants of enslaved people could even begin to pursue their ambitions freely. Women would wait longer still for the right to cast their ballot.

But in the end, the Founders also laid the groundwork for the very reforms they failed to enact. The principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution - however selectively applied at its genesis - created a foundation upon which abolitionists and suffragists would later would challenge injustice. The Constitution’s framework contained within it the mechanisms that ultimately made abolition possible. The same appeals to liberty and self-determination that justified America’s break from Britain would, decades later, be turned against the institution of slavery itself, and invoked to argue for the expansion of rights to those who had long been excluded.

In a bitter irony, even with the power of the Constitution behind them, both the abolition and suffrage movements required generations of struggle, proving once again that freedom was rarely granted without a fight, and that reform, as Chapman had put it, was "akin to taking a bone from a dog."

Potential in Action

So what are the present-day implications of ambition's chaotic history?

Much of ambition’s confusing, controversial reputation is unjustified and illegitimate. But it is controversial nonetheless, and as a result, treated like a pariah. Academics neglect it. Journalists reduce it to a buzzword. Organizations take it for granted. Ambition frequently sees the light of day only when it is summoned as a clumsy scapegoat to explain political misdeeds, criminal business ventures, and mad dashes for power.

The cost of this ignorance is high. It is a scientific axiom that to study and influence a problem it must be clearly formulated and deeply comprehended. But ambition - one of the most powerful forces driving human behavior and decision making - remains poorly defined, seldom studied, and rarely discussed with nuance. Without a clear grasp of ambition - its nature, role, mechanisms, and subtleties - we are left wanting. We cannot truly identify or differentiate it. We cannot learn how to appropriately cultivate and channel it. We cannot distinguish between the ambition that leads to greatness and the “ambition” that corrodes character. Thus we remain at its mercy, adrift in a world where ambition is ever-present but crudely examined, where we enact our striving instinct without truly understanding or controlling it. And ambition can be a fine servant, but a terrible master.

As human beings we are destined to contend with possibility. In the story of our lives, at any moment we exist in one place and are moving toward another. The direction of that movement is shaped, in large part, by our beliefs — by what we see as possible, desirable, or within our reach. Our fragmentary understanding of ambition and its convoluted, controversial history undoubtedly fuels the presumption, even if it is subconscious, that it is an untrustworthy guide in our story. Does that make us less likely to improve our circumstances, or to even bother trying? Does guilt around our own ambition bleed into unhelpful attitudes like perfectionism and “impostor syndrome?” How much of our potential are we leaving unrealized because we have been conditioned to mistrust our own striving?

Misunderstanding ambition also makes us more vulnerable to its hazards. Without a clear sense of how to regulate it, we risk overplaying the strength, ignoring the implications of “flying too low,” and failing to temper it with the right prescription of virtues, behaviors, and values. We can't define what magnitude of ambition is right for us, nor understand the associated repercussions and responsibilities. Worse, rather than master our own ambition, we risk becoming its slave and overcommitting to the wrong pursuits, pursuing money, acclaim, or achievement for their own sake, or allowing that potent energy to leak into unproductive diversions like accumulating likes, followers, possessions, and empty admiration.

This muddy conception also impacts how we see the world and those around us. Some remnant of the “ambition as sin” and “virtuous vice” ideology persists in our cultural subconscious. Are we more likely to discourage others from striving — to cut down tall poppies, drag down other crabs in the bucket, enforce the “Law of Jante,” and perpetuate other mediocrity-enforcing mechanisms? Is it easier to falsely conflate ambition with the desire for power, avarice, or Machiavellian scheming? Has it left us unsympathetic toward hardworking high achievers, yearning to see them fall, poking holes in their reputation, and basking in schadenfreude if their wings are melted by the sun?

We've inherited a version of ambition so full of contradiction and confusion that we scarcely know what to make of it. We are uncertain about our own striving instinct. No two people can agree on its character. No two definitions are the same. It is recognized but rarely recommended. It drives our personal pursuits, economic system, and cultural narrative, yet we speak about it in euphemism and hushed tones. We are left to believe our central ambition - our drive to achieve, improve, create, and earn our standing in the world - is somehow a flaw in the human condition. That it is a driver of behavior yet a source of shame.

These attitudes toward ambition are not only false, they are anti-truths, and they suggest we are, individually and collectively, failing to make the most of our gifts, energy, and ingenuity.

Ambition is human potential in action. It is a constant undercurrent in the story of our species. It may amplify our flaws, but it is certainly responsible for every breakthrough, every discovery, every improvement in our quality of life. Ambition is the fuel of our progress. It inspires us to innovate, explore, persevere, and rise to challenges. If we learn anything from this brief history, it is that we have no real reason to be ashamed of our striving instinct. Entirely the opposite is true.

Ambition is not something to punish, suppress, ignore, or explain away. It is something to understand, refine, and wield with intention and purpose. For centuries, we have struggled to define its role in human life, vacillating between reverence and suspicion, between praise and condemnation. But history makes one thing clear: when ambition is stifled, so too is progress. In the end, the true sin is not ambition — it is the suppression of human potential.

That’s all for this edition of The Executive Coaching Newsletter. To stay up to date as I release new articles, pose new questions, discover new research, and explore practical applications of these ideas, subscribe to this newsletter — click here or enter your email below:

Enjoy this article? Share it with a friend:

A version of this article was originally published on my now-defunct blog BringAmbition.com on March 28, 2022.